Page Intérieure

Creating images of exile

The act of portraiture is never trivial: photographers know this, and so do those who are being portrayed. Offering a reflection of yourself in a few fractions of a second is an exercise which, if you submit to it sincerely, is no easy thing. What a photographer hopes to capture, by allowing the subject to forget that the lens is turning him or her into an image, is an instantaneous capture, a ‘time T’ representative of that subject. When the intention is to express exile, the person in front of the lens brings with him or her more than a face: they bring a body, a journey, a crossing.

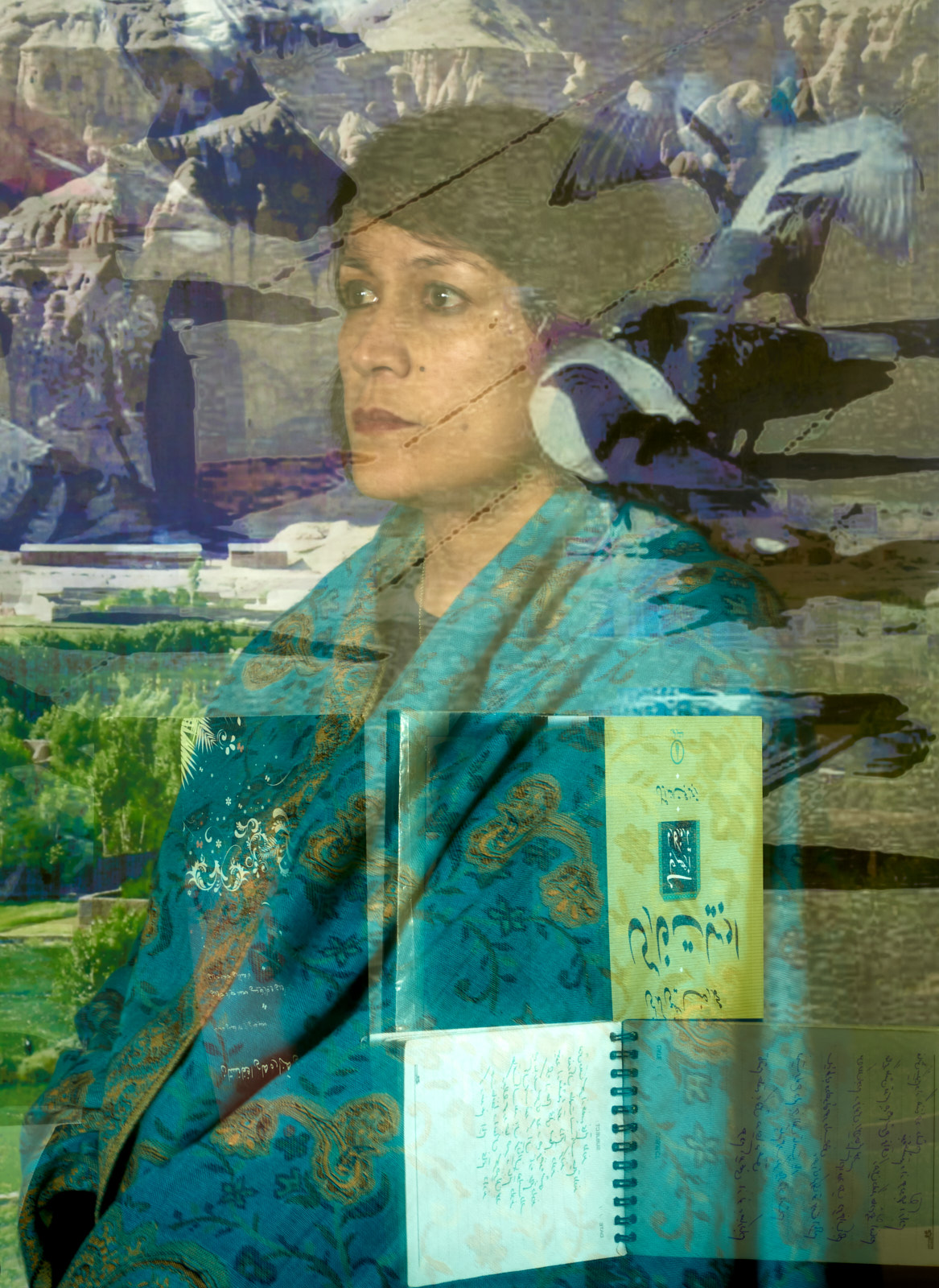

Fractions of a second in a classic portrait are no longer enough, and the photo frame suddenly becomes too narrow. Showing exile, after all, is the opposite of a ‘time T’: it is a long time and an immense space. ‘Time T’ would be a betrayal because it would reduce the identity of the person photographed to the constraint under which he or she has been placed. This is why all the thought given to the procedure has been obsessively devoted to showing more than the present, by restoring and making room for the layers of the individual history of each of the people photographed. And above all, there should be no shadow: recognizable or not, the face had to remain fully lit.

Extending time is a way to fit more elements into a single image. But it is also a way of making room for movement, the breath of life, the unexpected. These photos of several seconds are all crossings involving two people, a journey through the different dimensions of the subject’s personal history, a moment of shared intimacy. The portrait is then responsible for much more than the face. Or rather, the face becomes the focal point of a mental image with multiple ramifications, when the body becomes the receptacle of the story being told. This moment of sharing is built out of sight, before the button on the camera is pressed. The composition of the portrait becomes, unlike with conventional portraits, a very thoughtful exercise, a meticulous set-up, a construction, assembled entirely at the time of the shooting, without the possibility of subsequent modification or photomontage.

As we work together hanging the photos that the subjects of the photo have entrusted to me and that I have enlarged, and then arranging the objects that they have brought along, we start to speak. Sometimes immediately, sometimes in a more balanced, even timid fashion. The way in which contact is established, the density of the verbal exchange and the more or less committed way in which the elements of the photo are set up create an atmosphere faithful to the photographed subject’s being-in-the-world. This impression is generally found later, in the appearance of the person, in his or her way of inhabiting the frame of the photo and appropriating the ‘living’ space defined by the prior arrangement of the images and objects. In this recreated space, this world in itself, the subject must (re)discover his or her place.

Exile in the transparency of the present

The first photo, which is very rarely the one that will be chosen, is important, because it is the moment when the person sees the concrete result of what the process has produced, and realizes that the two of us are simultaneously spectators of the transparencies which happen to be produced and actors of the result obtained. If my role is to manage the timing which produces the transparency, the subject has an essential influence on the result: through movement or immobility, facial expression, and the colour of the skin or the tones of the photos that they have chosen.

Chance is a paintbrush that allows you to sketch out other perspectives. A partial covering of the image of the destroyed house with that of the host university, for example, is neither a reduction nor an erasure, but rather a dialogue between different temporalities, and the link between them is crystallized in a smile. The mixture is sometimes less explicit, but no less evocative, as when the verdant vegetation of Bujumbura merges into the snowy branches of Paris. There are also little miracles, as when the faces of demonstrators become fixed on the patterns of a floral dress to offer an image that is both poetic and political. Each photo conceals secrets which sometimes appeared belatedly and which the reader will enjoy unearthing with each new observation.

From this point of view, the work of processing the photographs played a ‘revealing’ role in the literal sense, comparable to the development of an analogue image: it involved modifying the basic characteristics of the photo (luminosity, contrast, etc.), which made it possible to express the full potential of each image.

‘If the photo is good’, to quote the singer Barbara, the image will symbolically give every individual a face and a place in the community of researchers of which they have never ceased to be a part, but also in their host country where they must have their place as full citizens. I am delighted to have been the privileged witness of these remarkable journeys and I thank Pascale Laborier for suggesting this project to me, making possible so many rare moments. Each of these meetings gave me a clearer awareness than before, perhaps a more embodied sense, of the fragility of values which, too often when we live in (relative) West European comfort, appear to be under threat only in other parts of the world.

If some of the power imparted to me by these researchers, accompanying the words with which they have described their exile, can reach the viewers of these photos, the goal will have been achieved.